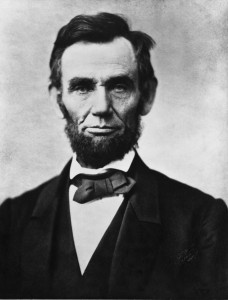

Pulitzer Prize winner Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book Team of Rivals paints a portrait of the American Civil War and the men who led our nation at the time. This well documented manuscript uses personal letters, full of insights and perceptions you won’t find in any history book. After reading these unbiased accounts of all involved in the leadership of our country at that time I’m convinced Abraham Lincoln was more than a political genius, he was a compassionate, just, fair, and moral humanitarian.

Blessed with the ability not to take criticism personally, his thoughts were only for the good of the country. Personal grievances or offenses that would have weighed down and obscured decisions of lesser men never hindered him from making wise choices. Always willing to go the extra mile and give others the benefit of the doubt, Lincoln knew when to be compassionate and when to stand strong. How else could he have persuaded his rivals to become his cabinet members and help him lead a country in turmoil? These learned statesmen had desired the coveted role of president themselves and were chagrinned to lose to a backwoods, self educated lawyer full of anecdotes and folksy stories, who looked more like a cartoon character than a political leader. However, each came to respect and admire him beyond anticipation and openly wept when he died.

Lincoln knew his Bible inside and out – and more importantly the principles it promoted. For example when one complained to him about the weakness of a certain cabinet member Lincoln said, “Go home my friend and read the tenth verse of the thirtieth chapter of Proverbs!” The verse says not to accuse a servant to his master unless you be the one found guilty.

Lincoln knew his Bible inside and out – and more importantly the principles it promoted. For example when one complained to him about the weakness of a certain cabinet member Lincoln said, “Go home my friend and read the tenth verse of the thirtieth chapter of Proverbs!” The verse says not to accuse a servant to his master unless you be the one found guilty.

As the war raged on, Lincoln’s religious reverence and belief in God increased. Lincoln knew the Civil War was in the hands of a higher power. He may not have attended church regularly or “kept the Sabbath scrupulously” his friend Swett observed, “but he believed in God as much as the most approved Church member.” Lincoln was “full of religion” and belief in “the great laws of truth, the rigid discharge of duty, and his accountability to God.”

During his Second Inaugural address Lincoln profoundly recognized that both the North and South had read the same Bible and prayed to the same God, and each invoked God’s aid against the other. However, he said, “…judge not that you be not judged…The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purpose.”

Lincoln never condemned the South for an inability to end slavery when he himself knew of no easy solution. As victory for the North drew near Lincoln urged his fellow countrymen: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

When the South did surrender Lincoln instructed Grant to let the Confederate soldiers keep their sidearms, horses, and baggage, and let them return to their homes undisturbed by Union authorities. Unfortunately, the South did not know what an ally they had in Lincoln. When he was assassinated, just weeks after his Second Inaugural address and the South’s defeat, the southern born Blairs wrote, “Those of southern sympathies know now they have lost a friend willing – and more powerful to protect and serve them than they can now ever hope to find again.” Lincoln’s death was considered, “the heaviest blow which has ever fallen upon the people of the South.”

When just twenty-three Lincoln wrote, “I have no other ambition so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem. How far I shall succeed in gratifying this ambition is yet to be developed.” I think he far surpassed his or anyone else’s expectations.

In 1909 Tolstoy summed up Lincoln’s greatness by saying, “…Lincoln was a humanitarian as broad as the world. He was bigger than his country…We are still too near his greatness but after a few centuries more our posterity will find him considerable bigger than we do.”

Well, centuries have passed and I think Tolstoy was right. Today’s politicians could learn a lot from Lincoln’s legacy.